The chapter entitled The Fiat G.91 pays heed to Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s commentary on the role of women in liberation wars, in which we see rare interviews with women freedom fighters from the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo), who are in the midst of countering napalm attacks by Nato G.91 aircraft. Meanwhile the Liberian government has decided to encircle the workers’ quarters with heavily armed soldiers. In Lamco, Liberia, 1966, Olsson introduces suspenseful footage of a strike in the Liberian town of Nimba where the Swedish firm Lamco (Liberian-American-Swedish minerals company) is using coercive measures to stop its employees from striking. There are also chapters dedicated to places and political parties, such as Rhodesia, featuring an infuriating interview with a white man in what is now Zimbabwe as he basks in unabashed racism while referring to his man servant as a “stupid thing”, all the while holding forth on the impending end of white privilege and his fears of a violent reckoning. Olsson provides emotional and psychological theses on African decolonisation, such as Indifference, in which a young South African professor speaks of five years spent in jail and the lack of feeling that liberation produced in him That Poverty of Spirit, in which a Scandinavian missionary couple sheepishly holds forth on changing African culture and values under the thin veil of Christianity and then Defeat, which graphically shows Portuguese soldiers suffering heavy casualties in the Guinea Bissau war of independence. The chapters that follow build on a variety of themes using quotations from Concerning Violence and Colonial War and Mental Disorders, the first and last chapters of The Wretched of the Earth. As she recites, Fanon’s words are also shown as text on the screen in a large serif font. This footage is juxtaposed with that of white, pre-pubescent boys playing golf as African caddies follow them around carrying their clubs.Ī throaty and assertive rendition of lines such as, “Decolonisation, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a programme of complete disorder,” is delivered by singer, songwriter and activist Lauryn Hill, who reads Fanon’s passages on decolonisation, nationalism and violence. This is the first scene out of the nine, titled Decolonization, and focuses on the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in 1977 as it carries out a stealth attack on the Portuguese-ruled and oil-rich Cabinda province in Congo. This footage is reminiscent of Coppola’s war scenes in Apocalypse Now, but the illusion is immediately shattered as the camera closes in and holds on the face of a murdered cow, blood slowly trickling down from her nostrils. The opening sequence offers a brief thrill which is immediately appropriated: helicopters whir in the air and soldiers shoot down terrified cows in a vast and lush field. The film’s subtitle, Nine Scenes from the Anti-Imperialistic Self-Defense, reflects Olsson’s investment in making Fanon’s theory relevant and up-to-date. This has often proven to be one of the most violent episodes in post-colonial history, and Fanon is its most articulate philosopher.

Olsson’s interest is in decolonisation – that short yet potent moment at the tail end of an anti-colonial war followed by the transfer of power when the new nation comes into being.

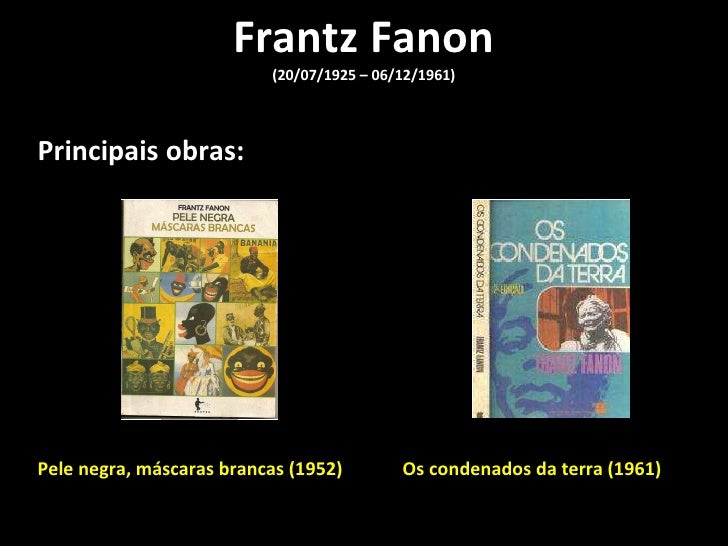

I had the impression that we were being provided with a visual exegesis on Fanon’s famous, misunderstood, and over-read text about violence, and that the images, in fact, served to bolster, or rather, offer, a kind of choreography to the text. Relying yet again on possibly forgotten footage from Swedish archives, the film has been anchored in Martinican psychiatrist and anti-colonial thinker Frantz Fanon’s controversial essay, Concerning Violence, from his 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth. Concerning Violence is a completely different beast.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)